Srivatsa Ramaswami on the Fundamental Intentions of Yoga

- —Laurie Hyland Robertson

- Jan 14, 2019

- 12 min read

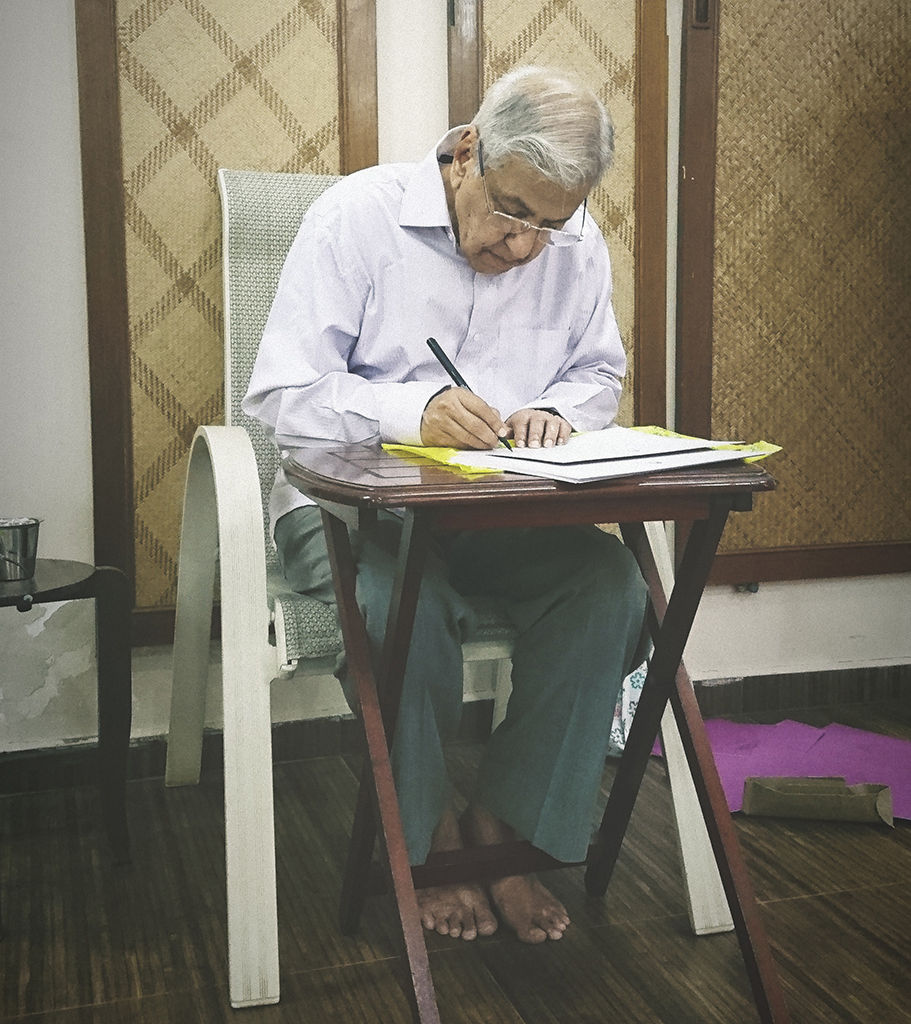

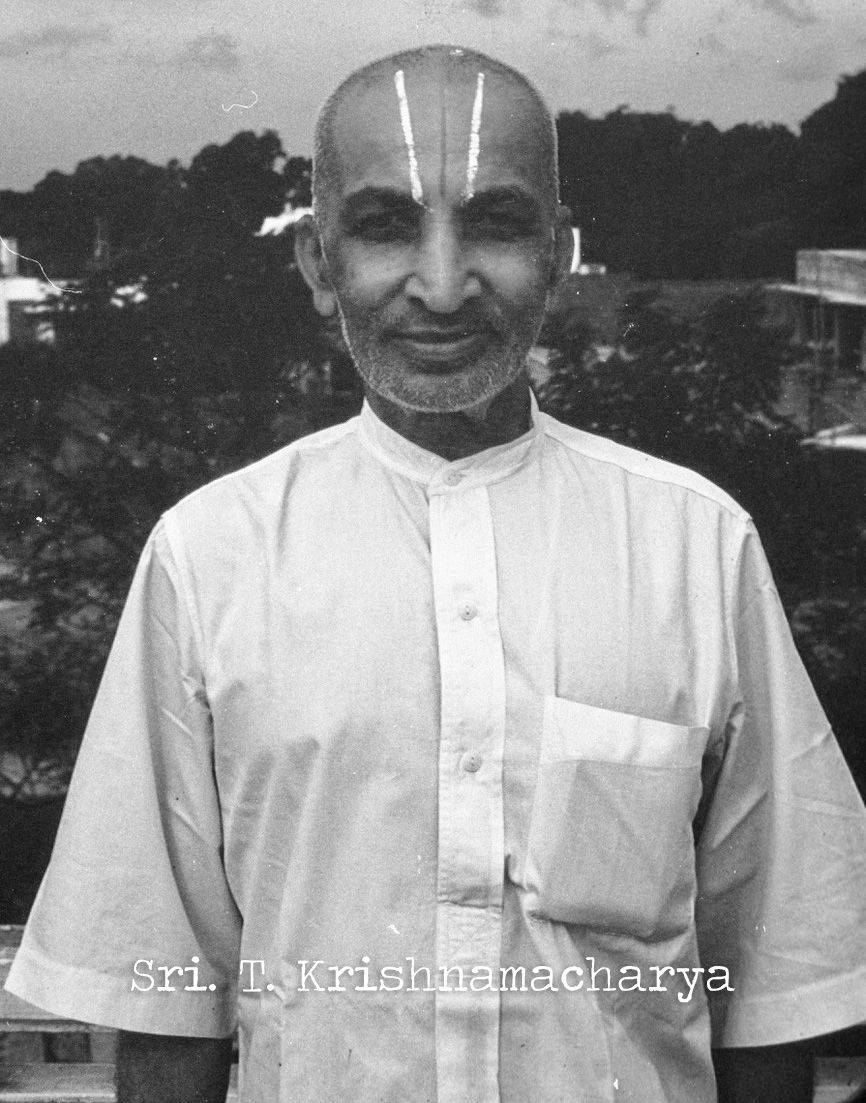

In August of 2018, I had the rare opportunity to talk with Srivatsa Ramaswami, long-time student of T. Krishnamacharya and now a well-known and loved teacher in his own right. In addition to translating the book mentioned below, Ramaswami has authored Basic Tenets of Patanjala Yoga, The Complete Book of Vinyasa Yoga, and Yoga for the Three Stages of Life. Originally from Chennai, India, he has the unique perspective born of 30 years of dedicated, continuous study with his guru.

In a timely discussion, Ramaswami shared his thoughts on yoga teaching and the way yoga therapy is practiced today. Do we miss something essential when we apply yoga as therapy, ending up with at best a sketched outline of the possibilities for reduced suffering?

Following is an excerpt from our conversation. It has been lightly edited for ease of reading. —Laurie Hyland Robertson

Laurie: I’d love to hear about Sri Krishnamacharya’s lesser known ideas about yoga as therapy.

Ramaswami: In one of Krishnamacharya’s books, Nathamuni’s Yoga Rahasya, in the first chapter, he refers to six koshas. The body is called the shatkoshtika sharira— shat means six, kosha means a bag or a sack. Your body is made of six important sacks or bags, organs in the body. Krishnamacharya referred to the six organs slightly differently during my studies with him. Two koshas are there in the thoracic cavity, vaksha sthala. They are the hridaya kosha—hridaya means heart, the heart bag, you see, and actually the heart is contained in a bag, the pericardium. It’s a self-contained unit, a lot of things are happening inside, but it is virtually sealed from its environment.

Likewise, you’ve got another important kosha in this area called the svasa kosha. Svasa means breathing, so the lungs are the breathing bag. Then when you come down, in the abdomen, we’ve got the anna kosha, “food bag,” which is the stomach. Then farther down, in the pelvic area, we’ve got three more koshas. One is known as the mala kosha, the large intestines. They’re also a bag—these are tubular koshas. Then we also have mutra kosha. Mutra is urine, so the mutra kosha is the bladder, also a bag. Then we have the garba kosha. Garba means the fetus, so garba kosha means the fetus bag, or the uterus. These are the six koshas referred to by Krishnamacharya.

Then each one of them maintains a subsystem. The hridaya kosha is responsible for maintaining rakta sanchara. Rakta means blood, sanchara means movement, so this kosha is responsible for maintaining blood circulation all through the body. Then you’ve got the lungs, the svasa kosha, they are responsible for maintaining respiration all through the body. Then we’ve got the anna kosha to digest the food and mala kosha for the elimination process. Then we’ve got the mutra kosha—the urinary system. And then finally we’ve got the garba kosha. These are the six important organs. Each one maintains an important function. One of the views is that yoga specifically targets these six koshas and tries to maintain the health of these organs. Towards that, there are a number of yogic exercises which can be used to specifically target these six important organs. There are certain procedures that are available to work with the heart, some with the lungs, some with the stomach, and some more with the pelvic organs—the uterus and others. That is why we’ve got so many procedures other than asanas in yoga. We’ve got pranayama mainly to take care of the two important organs in the chest—the heart and the lungs. Breathing affects not only the lungs, it also very much affects the heart; modern physiology explains that breathing is responsible for the venous return of the blood. Then we get to the stomach, and there are certain important abdominal exercises that you find in yoga. Then the pelvic organs are there— again, different procedures are available. Krishnamacharya used to stress these a lot. He would say that if you are able to take care of these six important koshas, then you will be able to maintain health for a much, much longer period of time.

Another view he used to express is that the six important koshas have got to maintain their positional integrity. Each one has got a definite position in the body, and the center of these organs should be kept at the same position as far as possible. As we get older, because of postural deficiencies, the muscle tone weakens— the heart loses muscle tone, for example, and the supporting musculature also starts losing muscle tone. Over a period of time, the organs tend to get displaced from their original positions. This phenomenon you find especially with the pelvic organs—prolapse of the uterus, prolapse of the rectum, and all that.

Taking all these factors into consideration, you would say that asanas are good, but not good enough. That is why in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika we don’t have only asanas—the second chapter is completely on pranayama kumbhaka [breath-holding], and the third chapter is completely on various mudras [seals], which help us to access many of the internal koshas. In those ways, we are able to maintain health for a longer period of time. The whole idea is that a yoga practice should not be confined only to asanas, but it should be extended to a fair amount of pranayama practice and also proper use of the mudras. Mudras include even inversions. Inversions are also very important because, as I told you, the internal organs get displaced from their original positions. So, on a regular basis, the yogis in the olden days used to keep their bodies upside down in the viparita karani [inversion, with head on the floor] mudras. The two important mudras are the sirsasana and sarvangasana—headstand and shoulderstand.

These are the various procedures that are available to take care of the important internal organs. If the yoga practice is developed in such a way that you don’t merely concentrate on asanas alone, but also on more and more of vinyasas—breathing when you do your asana practice, then a good stint of pranayama practice, and you use along with that the various mudras that are mentioned in the yoga texts—then you get a much more comprehensive yoga practice for health. It may not be exactly a therapeutic approach, but it is a health approach, and this is what those people in the past had done. The whole idea was in the olden days, the yogis had to take care of their own health, so they had to find out ways and means by which they’d be able to maintain good health all through their life. And these procedures, all of them are very unique to yoga. Like the many different types of breathing. Who breathes in the throat? Throat breathing is unique for yoga. Somebody who comes to yoga class, the first time you ask them to do ujjayi breathing, this will be the first time they will have done it—they never would have done ujjayi breathing in their life. And similarly for headstand. It is very unique. You’ve got to understand the various aspects of yoga practice and then use all of them so that you will be able to get the best out of the system from the health point of view.

Laurie: You’ve said that the yogis of old were using these practices as self-care partly because that is what was available to them. Even assuming that a yoga teacher or a yoga therapist is serving as a guide rather than dictating practices, how does that work, the idea of yoga as something that someone explores for themselves as this essentially internal work, and yoga as therapy? How do those two ideas fit together, and how does that fit in with your methods?

Ramaswami: The whole thing is that the way yoga is taught will have to be more inclusive. You can’t merely teach asanas every day. Two years you can study asanas, 3 years you can study asanas. Thereafter, you must start trying to understand what else is available. Afterwards you go for your pranayama practice, then you do your mudras. . . . The yoga offers much more than asana! It’s for your overall health. I’m not saying that asanas are bad. My teacher, Krishnamacharya, taught hundreds and scores of asanas, hundreds of vinyasas, so asana practice is very good. But what he would say is that this is not sufficient.

Every day when I went to study with him, we would take about 50% of the time for asanas, and the other 50% of the time would be for a little bit of pranayama, little bit of chanting, little bit of philosophy, whatever. It should be comprehensive. You can’t get the best out of the yoga by merely doing asanas. It’s not as though we neglect asanas, we give a lot of importance to asanas. But in addition to that, you must create interest in the students to practice the other aspects of Hatha Yoga like pranayama and then the mudras. That’s how I studied, that’s how Krishnamacharya taught us.

Laurie: How would he—and you—individualize the practices for different people who had similar conditions?

Ramaswami: There are three different groups, according to my guru. There is the yoga that you teach to the first stage of life—the vriddhi krama [the growth stages]—then the mid-part of life, when we are not growing anymore but maintaining. The biggest part of life, the whole emphasis, should be to maintain good health, and then in old age we must prepare ourselves for the end. There is no point in doing the same kind of yoga that I did when I was young as a kid, when I am old. It’s not correct, obviously it doesn’t work. Even in our daily life, that’s not the way we do. Yoga will have to be modified accordingly so that is why he would call the yoga vriddhi krama, sthiti krama, and laya krama.

Vriddhi krama is the type of yoga that you do during growth, so up to the age of 20, 21 or so, during which time the whole approach should be to help to improve the blood circulation, and then the prana circulation, so that the growth will be good. During the midpart of life, you want to maintain good health. Whatever you want to achieve in life can be achieved during the mid-part of life, so you’ve got to maintain good physical and mental health. For that, what are the various things you’ve got to do? And then finally during old age, a certain amount of philosophy will be helpful to be able to prepare yourself for the end. This is the broad approach, and then individually, people will come because of specific conditions. We find out what their specific problems are, and then we use plenty of vinyasas for specific conditions. Mostly if there is a problem with the skeletal system, then naturally more asanas and vinyasas will be helpful. On the other hand, if people come with breathing problems, like people who suffer from bronchial asthma or sinusitis or hayfever, then certain pranayama processes can be helpful. For instance, if people suffer from bronchial asthma, the one pranayama that will be most useful will be the ujjayi breathing because ujjayi breathing resembles asthmatic breathing—it virtually simulates asthmatic breathing. If you have a problem of constant sneezing, then kapalabhati [skull-shining breath] will be very helpful. There are specific procedures that are available for specific conditions. We can try to find out which one will be good and then come up with solutions for individuals.

Laurie: What are your thoughts on yoga “for” this condition or that one? Do we get dangerously close to addressing symptoms rather than the whole of the person?

Ramaswami: Ultimately we’ve got to find out a way to help a particular patient, right? We’ve got to study the particular patient, who may have a number of problems. Maybe a breathing problem will be there, the blood pressure may be high, maybe a person will be obese or a person may be depressed. So we study an individual patient and then try to find out what are the techniques that are available that can be applied to this particular individual. Unfortunately,many of the techniques I told you about earlier have to be learned over a period of time. Supposing you ask a patient to do ujjayi breathing. They will not be able to do that. Ideally, you’ve got to prepare yourself, which itself takes a certain amount of time. That is why the best results you get from yoga is when you start when you are healthy. When you are healthy, you start practicing so that you don’t fall sick.Laurie: It’s probably a universal human condition that we often don’t undertake methods to make ourselves healthy.Prevention is not an easy sell, so what do we do when someone arrives in our therapy suite or in our therapy class and can’t access ujjayi breathing?Ramaswami: If you merely approach yoga as something which can be applied only for therapy, then you lose. My own impression is that yoga was not meant as a therapeutic tool. Yoga was meant as a health-providing tool. Suppose I’m a yoga therapist. In addition to my wanting to help people with individual conditions, if I am going to teach yoga, I must also try to teach the other aspects of yoga, even for healthy people. If somebody has already got an ailment, then naturally you’ve got to address that particular condition, but that’s not the only thing. That’s how most of the medical doctors do. They only treat the patient; they don’t tell you how to maintain good health. But yoga is much more than merely tweaking here and there.Laurie: What’s your opinion on the way yoga therapy is being practiced today?Ramaswami: What I would say is that it’s good, but the yoga therapists will be able to contribute much more if they are able to teach the whole yoga system to even healthy people. How many people come to you for therapy? Maybe 30%. The other 70% of the people are healthy people. They want to maintain good health.

Sometimes yoga is taught as if it is a workout. Instead of that, in addition to teaching them all the asanas, we can also teach them the other things Hatha Yoga practice includes—asana, pranayama, and the mudras. You’ve got to teach all of them, and you must also understand why it is being done. This is what Krishnamacharya did.There is a reason why mudras are mentioned. There is an important reason why pranayama is mentioned. It is not a mere exercise of taking a deep breath and exhaling. It has got a tremendous amount of influence. With pranayama, you are able to improve the blood circulation.The venous return of the blood is substantially increased if you are able to take a deep inhalation and hold the breath. That not only improves the exchange of gas and the blood in the lungs, it also improves the venous return of the blood, and to that extent it reduces the strain on the heart! In addition to that, think about uddiyana bandha [abdominal lock] and kapalabhati. The pericardium is directly connected to the diaphragm, so when you do kapalabhati regularly, you are able to work with the heart. You are able to exercise the heart—you can help the heart by doing your uddiyana bandha and kapalabhati and all.

In fact, my teacher used to say, a yogi should not strain the heart. If he found a student getting short of breath, he would ask you to take rest. The whole idea is the heart should not be strained and everything that you can do to help the heart do its function, you must do. One of the things is pranayama. The other things are the mudras. All of them help the heart to do its function better. So a better understanding of the mudras and the pranayama is necessary. What does it do physiologically? That we have got to understand. Then we will have a better appreciation for the various procedures that are mentioned in yoga. Normally, when we do pranayama and all the mudras, we don’t pay much attention to it-we just do it because it is mentioned in the yoga texts, that’s about all. Or, because it looks very impressive. Many people do their uddiyana bandha, take a picture of their abdomen, and they put it on Facebook. That’s good, but then, what does it do? I must be able to understand the benefit I get out of that.

Laurie: And that comes from the deep self-study and self-observation?

Ramaswami: That is right. Whenever you do something in yoga, you must try to understand what it does physiologically. These procedures are not normally found in other forms of exercise. Where do you find headstand? Where do you find shoulder stand? Where do you find the unusual breathing procedures? Where do you find abdominal exercises like your kapalabhati or uddiyana bandha, or agni sara [gastric fire enhancer]? These are all unique to yoga. If I do something unique to yoga, I must understand what does it do. You don’t have to completely follow the old texts when they say that this chakra is stimulated or prana goes through the sushumna. They are difficult to understand. Just take these things and then see what [they] do to your own system.

Laurie: That’s the ultimate in individualized therapy, right?

Ramaswami: Yes. Once you have all these tools, once you know how you are able to use them, most people can do it for themselves. When you don’t do any of these things, when you allow your body to get sick and then try to get a hold of yoga, many of the procedures in yoga are very difficult to do. You won’t be able to do them!

Pranayama you won’t be able to do. Your lung capacity is low, your chest is tight, so many things will stop you from being able to use the yoga procedures that are available for you. That is why awareness about the benefit of yoga should be given to yoga practitioners in the initial stages—they must know, “Why am I doing this?” YTT

Ramaswami teaches internationally on these concepts, including the six kosha model. Visit vinyasakrama.com for more information.

Comments